On the occasion of the broadcast of De Gaulle, le commencement on france.tv, Julien Pamart, director of photography, and Grégoire Ausina, colorist, share their insights and experiences working on this project.

Produced by Dana Hastier for France 2’s documentary unit and directed by Frédéric Brunnquell, this two-part series (each episode 52 minutes long) falls under the genre of docudrama—a term that encompasses a wide variety of films.

To describe what De Gaulle, le commencement is, I prefer to say it is a biopic about the youth of Charles de Gaulle. The film traces the journey and daily life of the young military officer during World War I. Wounded in 1914 on the Belgian front and later reported missing in 1916 at Verdun, he endured thirty-two months of painful captivity and made several attempts to escape from German fortresses.

Archival footage woven into the narrative helps situate the well-known milestones of the Great War throughout the story. While this era provides the backdrop for the film, the main focus is to reveal the personality and inner thoughts of the young officer De Gaulle. Although the writers—Frédéric Brunnquell and Emmanuel Salinger—drew extensively on historical documents to craft the script, which recounts De Gaulle’s experiences during this period, they also infused it with an epic dimension that influenced how I approached the film.

The Challenges of the Historical Film

From our very first preparatory discussions, Frédéric made it clear that he intended to stay as close as possible to his character—even inside his mind at times. The goal was not to film World War I itself, but rather to paint the portrait of a young man of that era, fascinated by war. This narrative choice shaped the entire filmmaking process, from the sequencing of scenes to the choreography between the camera and our de Gaulle, brilliantly portrayed by the generous actor Eliott Margueron.

It was also during these conversations with the director that I realized the scale of the challenge ahead. The references he cited were classics of cinema, yet the budgets allocated by France 2’s documentary unit were in no way comparable to those of the fiction department—even though we were shooting a fiction, a period film with battle scenes in sometimes complex sets!

We had to find solutions to ensure the film’s visual style aligned with the director’s expectations while respecting the constraints of production.

Charles de Gaulle in 1915 (Eliott Margueron)

A Staging Focused on Characters

Preparation is a stage I particularly enjoy because it allows me to gradually grasp the film the director envisions and to think about practical solutions to bring his ideas to life.

It was during the very first location scouting sessions that I noticed Frédéric’s meticulous attention to every detail and every prop, striving to authentically capture the reality of the World War I era. He didn’t want the film to be overwhelmed by the decorative aspects often associated with period pieces—he wanted it to feel “real.” I suggested framing the shots as if it were a contemporary film, focusing on the characters’ faces without hesitation, even if it meant cutting off parts of their headgear or uniforms. This approach seemed right to avoid the impression of a mere reconstruction and to stay as close as possible to our characters.

I decided to shoot with the Alexa Mini paired with a set of Primo lenses. I love the softness of the image created by the Panavision lenses combined with the texture of the Alexa’s sensor. The resulting images have an immediate cinematic quality that perfectly matched Frédéric’s references.

The Alexa Mini, with its robustness and ergonomic design, seemed like the best tool for working quickly and in often tight spaces—such as trenches or a dungeon. Additionally, due to its relative age, the rental cost was well-suited to the film’s budget.

Meticulous Attention to Every Detail

We shot exclusively in natural settings, and production designer Audrey Hernu truly brought out the best in each location. She met all our requests—even the most unusual ones, like the charred tree I imagined looming over our De Gaulle during a speech to his troops, or the different soil coloring in the trenches. I wanted the earth to look distinct for the sequences depicting the Battle of the Marne compared to those set in Verdun, even though both were filmed in the same location.

This meticulous attention to detail was shared by the rest of the artistic team: for the costumes, Louis Descols’ expert eye allowed the actors to wear their uniforms like a second skin. The Makeup and Hair teams, led by Sylvie Ferry and Melyssa Jacob, did not hesitate to ‘weather’ our actors using earth pigments selected together, achieving the most realistic effect possible and ensuring harmony with the film’s color palette.

A Tightly Organized Plan to Stick to the Schedule

It was during the technical scouting that we found the filming methodology that would allow us to meet the tight schedule: 20 days to shoot 90 minutes of film with a single camera, with archival footage accounting for about fifteen minutes spread across the two episodes. The shot breakdown was designed based on the possibility of lighting the sets with natural daylight. Some scenes relied on sequence shots, while others were rewritten by Frédéric, taking the sets into account to make the most of camera movements made possible by the geography of the locations—the layout of rooms in the family apartment, the trenches sometimes too narrow for a camera to pass through.

With Franklin Ohanessian, the first assistant director, we devised a filming organization that allowed us to pre-light the next day’s sets the evening before, ensuring we were as efficient as possible during shooting. This was feasible because we spent several days on most of our sets, which were grouped into three main blocks: a house (where we filmed both the family apartment and the officers’ offices), the trenches, and the fort that served as De Gaulle’s prison.

The electrical and grip team, though small given the nature of the project (one electrician plus an assistant, one grip plus an assistant, and an intern who worked tirelessly), had to organize themselves meticulously. While part of the team handled the current shot, the others prepared the upcoming sets. We also had to anticipate the distribution of equipment between the set and pre-lighting, as our lists were designed in line with the film’s budget.

These considerations applied not only to the lighting sources but also to how we would execute camera movements, as the film featured many tracking shots. We hadn’t rented a dolly, but my key grip, Vincent Trividic, skillfully managed with a few meters of track, a dolly platform, and a pneumatic bazooka to achieve the movements I had proposed to Frédéric. For several shots, we also used a Dana Dolly, which proved to be the right tool for filming the actors’ faces as they moved through the trenches.

Dust, Smoke, Colors: Capturing an Era

For the lighting, I started with the idea of enhancing the natural directions by using the existing daylight in the sets. Together with my gaffer, Sébastien Plessis, we experimented with evolving the lighting atmospheres from one scene to the next: sometimes, we used set elements (sheer curtains, frosted glass in certain windows) to diffuse the outside light, texture it, or give it a tint. Other times, we favored more direct lighting and heightened contrasts by “negative lighting” using flags or barn doors. We also relied on the natural diffusion of smoke to refine the texture of our images. The era lent itself to this—cigarettes, wood stoves, oil lamps, and the dust of the trenches all contributed. Our set dresser, Louise Huriet, played a crucial role in managing the smoke control. She was also the one we turned to for moving the oil lamps or candles in nighttime sequences. The use of these warm light sources, contrasting with daylight, perfectly complemented the horizon blue of the uniforms, enriching the film’s color palette.

Another decisive choice Frédéric and I made was to involve Grégoire Ausina from the very start of production. He would become far more than just the film’s colorist. This happened naturally—while Frédéric and I had never worked together before, we had both entrusted Grégoire with the color grading of several films. So, he joined the team during pre-production.

Julien Pamart

Choosing HDE

As a colorist, we don’t often get the chance to prepare for a shoot. On these ambitious films, we needed to find solutions to produce high-quality images with a fast setup. There was no room for error. I wanted Julien to be able to shoot in ArriRaw so we could freely develop the look of the image later. The fight sequences, day-for-night shots, and period sets demanded it. This was made possible by using HDE compression, which allowed camera assistants Laure Caniaux and Juliette Poirot to save time during backups. By reducing file size by about 40% during offloading, HDE enabled us to rotate cards with the limited stock we had.

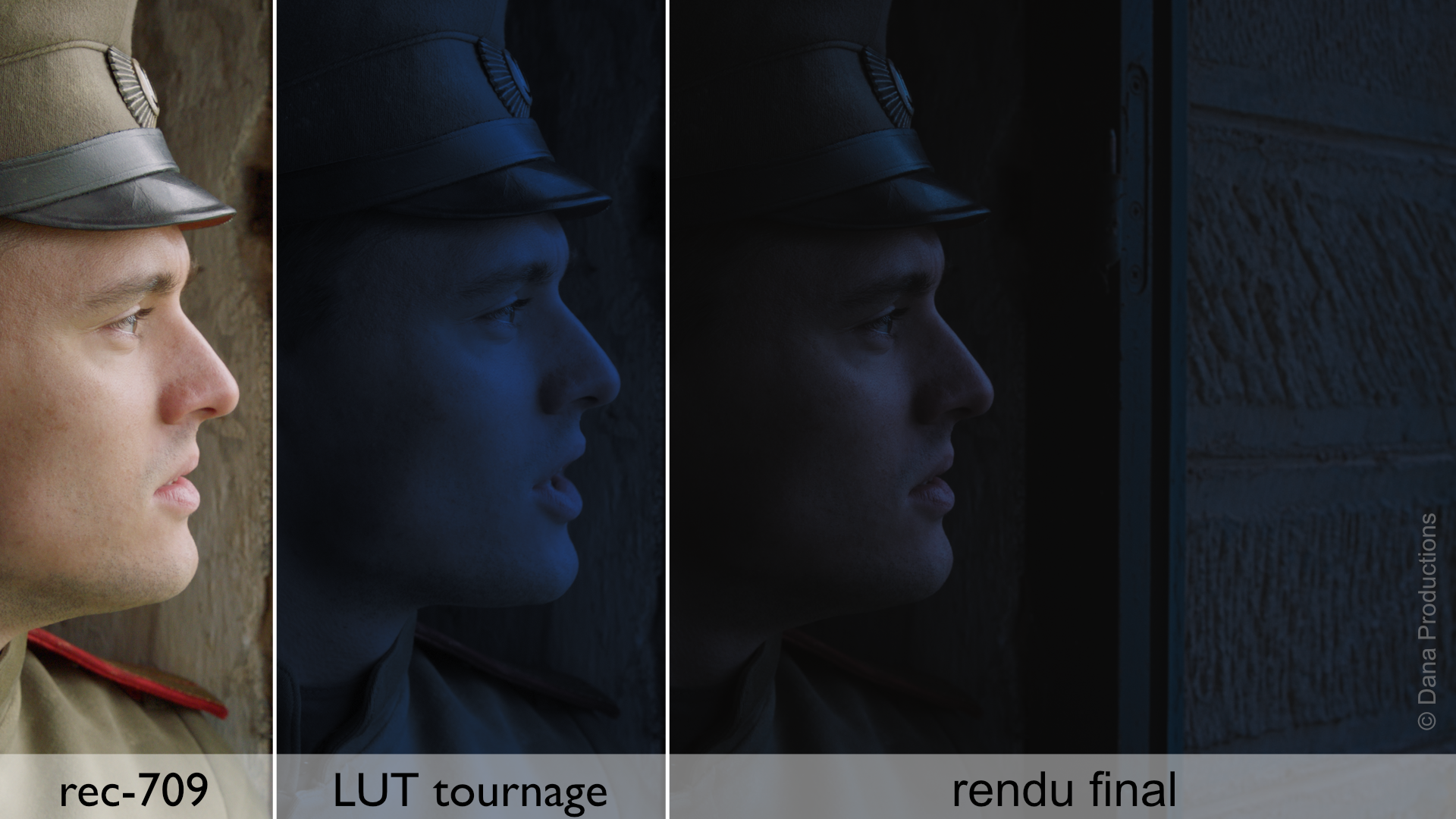

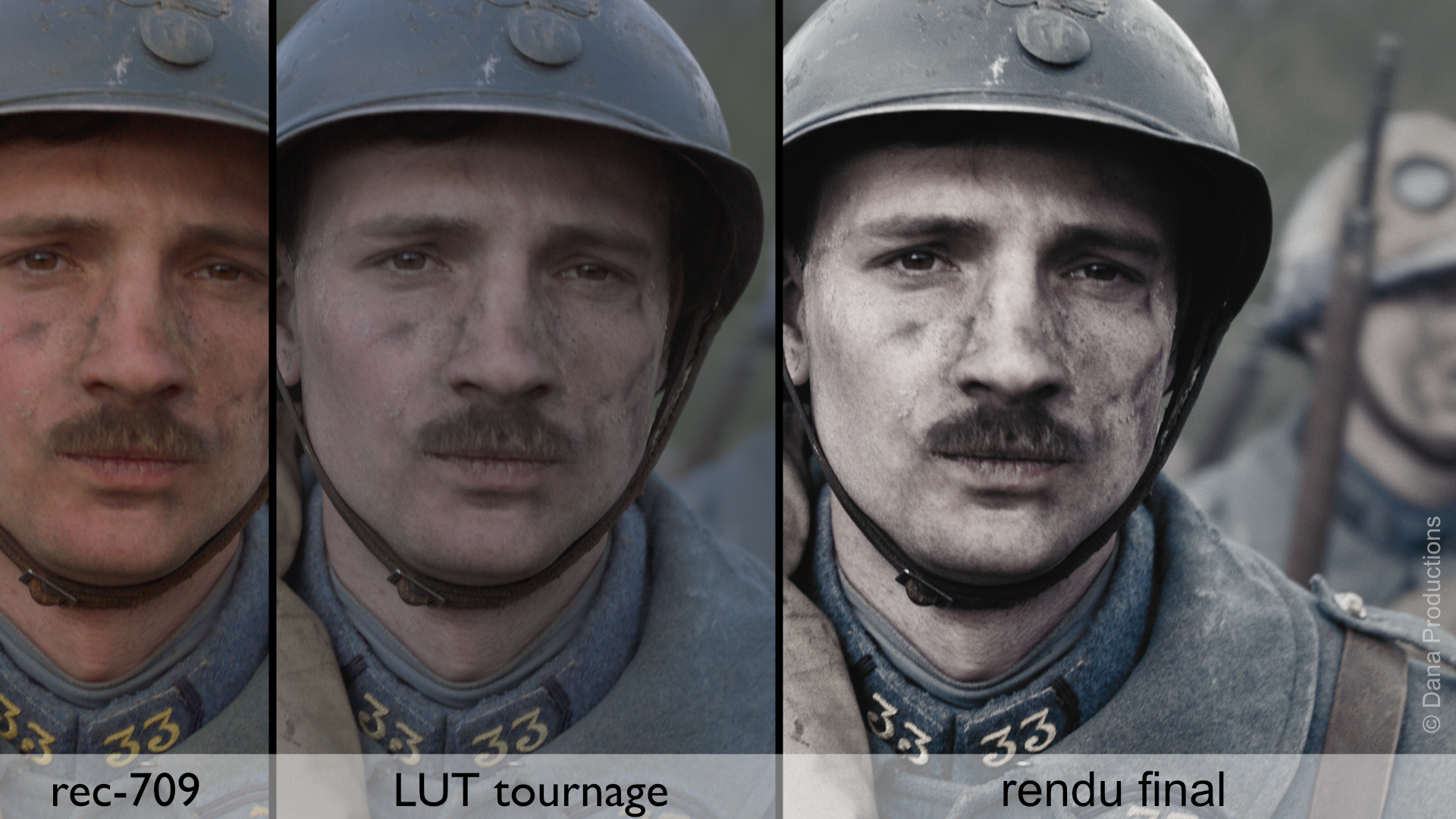

Three LUTs for Three Atmospheres To prepare for the shoot, I participated in camera tests, and we simulated the three distinct visual worlds for the two episodes. I then exported the three LUTs that Julien used during filming:

- A fairly natural LUT that toned down the overly electric colors compared to REC 709.

- A day-for-night LUT: Since production constraints made actual night or dawn shoots impossible, Julien and Frédéric decided to embrace the day-for-night convention but with special care.

- A LUT for the trench sequences: We aimed for a kind of “unbleached” look, with blue in the blacks and desaturated colors elsewhere.

For both the night and trench sequences, we adjusted the mid-gray to guide exposure in the right direction—subtly but effectively. The night LUT was slightly brighter to encourage Julien to underexpose, while the trench LUT was darker.

A Carefully Designed Shooting Workflow

During the shoot, I received the rushes every other day to secure them on LTO and decompress the HDE files. This workflow works, but it requires the right software licenses for offloading, so rental companies need to be well-prepared. HDE is clearly not often used, and this point needs to be emphasized. In post-production, you also need computer systems capable of handling this format in real time, as it demands significant resources. After decompression, an ARX file per image is much heavier to process than a standard MXF video file! In short, HDE lightens the shoot but weighs down post-production. It’s clever, but everyone needs to be fully aware of this.

I then synced the sound, applied the looks and optical crop presets based on the script supervisor Fanny Olivier’s reports, and generated proxies for editing. I could then notify Laure or Juliette on our dedicated WhatsApp group that they could format the shoot cards, which were in short supply. This communication channel was a great idea—much more practical than phone calls on set.

Before finalizing renders and sharing images with production, Julien and I agreed to review all the stills I had sent him just before. This allowed us to discuss what worked and what might need adjustment for the next day’s shoot. I was Julien’s eyes in Paris, and these few minutes at the end of the day helped me better understand the script supervisor’s reports. I could congratulate him on what went well or warn him about risky shots. These were moments of camaraderie where my experience as a camera operator allowed me to put myself in Julien’s shoes, encourage him, and think with him about the next day. He would then ask about the possibilities for retouching certain upcoming shots, knowing I would also handle some visual effects.

Final Grading: Adjustments to Support the Narrative

After the shoot, several months passed before the project returned to me for final grading. With Frédéric’s approval, Julien and I started with a grading session to discuss the first pass effectively, using our technical jargon. This was an opportunity to test the intensity of the looks in the narrative progression, refine the day-for-night shots that required a lot of attention, and perfect our initial intentions. The LUTs were solid foundations—deliberately more restrained than the final grade but distinct enough to guide everyone toward our choices. During the shoot, the art and HMC teams could work precisely, and intermediate screenings were much more comfortable than in REC 709.

For the second session, Frédéric joined us, and we agreed on most of the scenes. These collaborative moments, well-prepared, were a real pleasure for me. I’m often faced with images that need saving, but this time, I had the satisfying feeling of improving them, giving them a unique touch, and being in control.

Grégoire Ausina

“De Gaulle, le commencement” 2×52 min

Directed by: Frédéric Brunnquell

Produced by: Dana Productions for France 2

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the camera team for their unwavering motivation and professionalism throughout this project:

1st Assistant Camera: Laure Caniaux

2nd Assistant Camera: Juliette Poirot

Video Assistant: Marie Mourot

Gaffer: Sébastien Plessis

Electrician: Alexandre Hoareau

Key Grip: Vincent Trividic

Grips: Ludovic Jacques and Ludwig Mourier

Grip Intern: Nikolas Rocher

Equipment Rental: Panavision Paris

Camera: Arri Alexa Mini

Lenses: Primo SL