The term can be understood in two ways: how do we acquire knowledge and know-how, but also how are they transmitted?

Transmission is fundamental to the UCO. For the association’s founders, it seemed obvious to welcome young professionals wishing to move into photography.

The idea is that interactions between members encourage the dissemination of all the elements that characterize our profession: not only knowledge and experience, but also know-how and interpersonal skills.

Being myself this self-taught cinematographer trained in experience, kindness, open-mindedness and the good advice of my peers, I still wonder today how we come to practice this fascinating profession, which owes as much to our intuitions and our personal experiences as to a sum of cultural, technical and artistic expertise. This led me naturally to transmit my knowledge episodically a long time ago but more regularly in recent years and, teaching in a national public school, I wondered with a little bad spirit if the “art” schools were really capable of producing the artists and professionals of tomorrow.

I obviously do not have the answer, but this questioning reminds me of this postulate of Sigmund Freud, who in a text published in 1937 (“Analysis with end and analysis without end”) identified 3 impossible professions: to govern, to educate, to psychoanalyze. To which we could add by extension: instruct, or train! A mission that is indeed undoubtedly impossible because we know that basically the results of our efforts would prove to be partly unsatisfactory, because each student or learner has his or her own limits, which can be of any kind.

When we transmit our knowledge, how can we know to what extent the whole and scope of the knowledge we share will be assimilated? How can we guarantee to training institutions that their programs, often very selective, will produce filmmakers and technicians that will leave a lasting mark on their field? And according to what criteria should we evaluate this success?

Here again there is no certainty and on the other hand we can also consider, this is my case here, that even if despite all my efforts, all the knowledge transmitted will not be assimilated, there will always be something left, of which the learner will ultimately know what is most important to him, and there will above all be a human encounter, the impact of which we never can really measure, but which can turn decisive. We can also consider that the encounter also affects the trainer: Shouldn’t we, over the years, adapt our teaching to our audience? And isn’t it through the way our students apply and enhance their knowledge that we obtain the most valuable feedback on our effectiveness as a teacher?

To share and extend these reflections, I asked the members of UCO to respond to a completely non-scientific questionnaire whose purpose would be to establish a sort of profile of these training camera operators. Note that this is a multiple-choice questionnaire.

Profile(s)

– 24 of our members responded (out of a hundred members), being themselves teachers or trainers – we could therefore consider that a quarter of the UCO’s members have teaching experience. For a large majority of them (85%), training occupies between 10% and 25% of their professional time, 3 members dedicate between 25% and 50% of their activity to training.

– 3/4 work on a paid basis occasionally in various structures, 1/4 gives regular courses, most of the time in a single organization.

The interventions mainly concern initial training (students) in film/audiovisual schools (almost equally between public and private schools), much more than continuing training (aimed at employees).

Interventions are much rarer in the associative world and at university.

A good third party also shares their knowledge in an unpaid framework, through image education associations for example or online (personal blog, social network accounts, YouTube channel, etc.).

– Trainers are generally hired under the general scheme, almost equally with hiring under intermittent status, more rarely on invoice.

– Most (59%) of our members have been trainers for several years, 36% for between 10 and 20 years, only 1 of our members has been teaching for more than 20 years. The majority of respondents are required to design course materials.

– A good majority of those interviewed have taught abroad (Switzerland, Italy, China, Morocco, etc.) and/or in a foreign language, the vast majority in English (which can also be the case in France at ESRA, 3iS or FEMIS), more rarely in other languages (in Spanish at EICTV in Cuba, for example!).

The questionnaire also reveals that it’s not uncommon to stay in touch with students or interns. These contacts continue with some, who may become assistants or collaborators.

We can imagine that our way of managing a group, supervising students or trainees in a training situation is not so different from our way of uniting the image team in filming conditions.

How do you become a trainer?

In our professional environment, based on reputation, it is not surprising to find the habits of our milieu: interpersonal recommendations (word of mouth in short) are the most classic way to become a trainer, also by occasionally replacing colleagues or by supervising practical work in one’s former school. Hiring through unsolicited applications is rarer.

It should be noted that there is, strictly speaking, no specific training to become a trainer. While colleagues can guide us in designing a course or introduce us to a certain type of audience or even to the institution that employs us, trainers often find themselves alone when it comes to this state of mind that is pedagogy. On this subject, I believe that one is either a teacher or one is not. It is essential to have the desire to transmit and, ideally, to derive a certain personal satisfaction from it. It seems to me that the best training in pedagogy remains to have been a learner oneself, regardless of the learning method. Our trainers, for the most part, have a background that passes (in order of frequency) through the public sector, self-teaching, and then private schools. During our schooling, we have all encountered good and bad teachers, regardless of the subject taught. We have also all come across teachers or trainers whose expertise and attitude have been decisive, even if we do not always realize it immediately.

This is one of the immediate pleasures of teaching: the direct interaction with one’s audience through the object of transmission, when one feels that the concepts are understood intimately and implemented immediately. This is obviously less the case for our colleagues who share their technical and aesthetic knowledge via the internet, where feedback is not rare but not systematic, and in any case deferred. Perhaps coming into contact with the taste for teaching gives a taste for learning, and for some of us, a taste for passing on our knowledge in turn. The right framework then presents itself when the time comes… Let’s keep in mind that our profession essentially takes place on sets and behind a peephole.

A word about self-taught learning, a subject I know well: being self-taught can result from a choice or a situation, particularly if joining a very selective or expensive course was not an option, or even during a career change. This then requires mobilizing all of one’s resources and energy to transform each experience into a lesson, to learn and, above all, to evolve. Our professional sector is full of these individuals formed by their own determination and the chance of happy encounters.

Vocational training

The majority of those interviewed continue to train in our professional sector, mainly on equipment but also on post-production tools, and to a lesser extent on other professions in our sector: production, editing, screenwriting, etc.

It is difficult to determine whether trainers receive more training than their non-training counterparts. However, we can assume that they are aware of professional training programs, as many of the initial training institutions where they work are expanding their offerings for active professionals. Beyond acquiring new techniques or familiarizing themselves with new tools, training is also a time for introspection. Sometimes, the desire to train stems from a personal awakening or a period of professional stagnation. It is also an opportunity for professional encounters outside of a traditional “work” setting.

I would like to remind you here that in France professional vocational training is a right and that every french employee can benefit from it.

Interactions

During classes, practical work, and internships, students and interns bring their experiences, their practices, their sensibilities, and their desires. Listening to them always seems to me to be a precious moment, which allows us to get to know personalities, whether they are emerging or already well-established. There is sometimes a little apprehension, but also enthusiasm, freedom, and freshness in the way of approaching technical and artistic issues. On this point, vocational education has the particularity of being able to put us in contact with experienced professionals, whose perspective is most of the time already seasoned, which opens up new horizons.

These encounters have often led me to evolve my own pedagogical approach, because I find it stimulating to seek to improve the format of my presentations. But also because, in a certain way, visual production practices are evolving, and our students and trainees with them.

So many aspects of teaching practice that led me to the reflection that ultimately, to train one another is to train oneself.

What the UCO’s respondents added:

– Training means structuring your thinking to better transmit, and thus improve your own practice. A true virtuous circle if you are rigorous.

– It also means becoming aware of your own knowledge, and therefore knowing yourself better.

– It is first of all training in pedagogy, which is a very specific skill. Then, it is frequently going back to the fundamentals and sometimes (re)discovering more precise notions.

– It forces you to take a step back from your practices, your automatisms, to conceptualize them before transmitting them. Having to feed content streams leads me to stay on the lookout, so that I can then share my experiences in a more intense and in-depth way. For example, I very often take photos of specific lighting conditions, so that I can talk about them later in lighting courses. The same goes for the latest lighting or camera equipment, and with the latest real-time 3D lighting possibilities.

– Ideally (for students) it is even about showing our uncertainties and questions (cf. Bernard Stiegler).

– Training means learning to simply explain what we sometimes practice intuitively.

– Above all, it forces us to do analytical and reflective work on our practices and stay in touch with the new ways of understanding the world of the generations who will make the cinema of tomorrow.

– I train individuals who are not specifically targeting the field of image, who have varied levels and who, for the most part, are not interested in schooling. This forces me to question my own knowledge: what are the essential skills on a shoot? How can I provide them with ways to deepen their knowledge without intimidating them? (If none of them doze off while I explain depth of field, I consider that a success). The challenges of transmitting knowledge and supervising shoots require constant adaptation. Above all, it is a training focused on the human and relational aspect.

Here we are. Our main mission is to share our technical and artistic knowledge, although many resources are already widely available on the Internet. However, our in-person interactions with students and interns allow us to experience what characterizes our profession: know-how and interpersonal skills embodied by a personal, intuitive, emotional, and pragmatic approach to visualization.

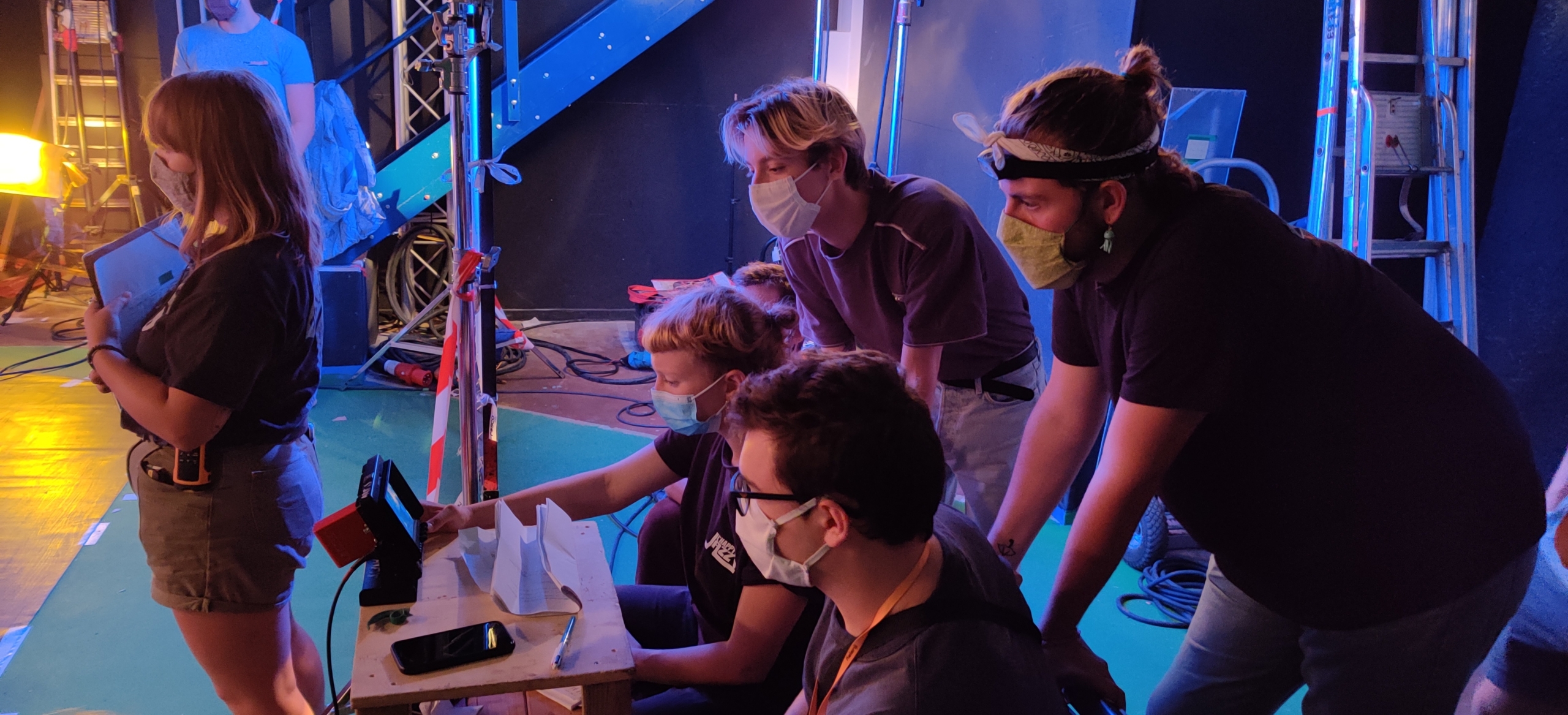

Photos taken during various lighting workshops given at ARFIS (Villeurbanne), now ESEC Lyon. Photos © UCO – Pascal Montjovent / Front page photo © UCO – Thomas Lallier