During a RED seminar at Camerimage, cinematographer Markus Förderer, ASC, delivered a detailed analysis of his work on Tim Fehlbaum’s *5 September*. Far from being a simple pastiche of the 1970s, he explained how, by juggling “detuned” lenses, multiple formats, and ingenious practical effects, he sought to blur the lines between archival footage, documentary, and fiction. This hybrid approach, where texture, contrast, and even screen flicker frequency were used to manipulate authenticity and serve a constant narrative tension, was achieved within a relatively tight budget, given the challenges of a historical film and the artistic ambitions of the script. The film revisits the hostage-taking of 10 Israeli athletes by the terrorist organization Black September during the Munich Olympics in September 1972, adopting the perspective of its media coverage by ABC Sports.  For the cinematographer, the main challenge was finding the right balance between the authenticity of the historical reconstruction and the creation of an original art direction, since the film remains a work of fiction and not a documentary. Förderer didn’t necessarily want to imitate the look of films from that era, nor did he want the costumes and sets to be too conspicuous, as this could distract the audience. But he also didn’t want to achieve an overly contemporary look, which would have broken the illusion of traveling back in time. At the heart of the art direction was the choice of lenses. Förderer is passionate about optics. “For me, the lens is the most important thing.” “Before even thinking about the camera or the format, I think about the lens through which I want the audience to see the film. This choice defines the ‘visual language.’ For September 5, he wasn’t looking for a perfect imitation, but a feeling.”

For the cinematographer, the main challenge was finding the right balance between the authenticity of the historical reconstruction and the creation of an original art direction, since the film remains a work of fiction and not a documentary. Förderer didn’t necessarily want to imitate the look of films from that era, nor did he want the costumes and sets to be too conspicuous, as this could distract the audience. But he also didn’t want to achieve an overly contemporary look, which would have broken the illusion of traveling back in time. At the heart of the art direction was the choice of lenses. Förderer is passionate about optics. “For me, the lens is the most important thing.” “Before even thinking about the camera or the format, I think about the lens through which I want the audience to see the film. This choice defines the ‘visual language.’ For September 5, he wasn’t looking for a perfect imitation, but a feeling.”

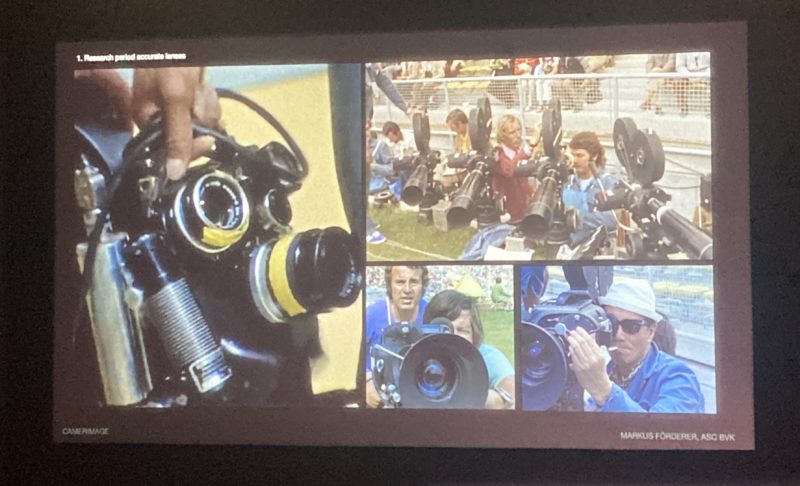

Research on the Lenses Used at the Time

He conducted extensive research to determine which cameras and lenses were used at the time to capture sporting events. In fact, there was a special 1972 Olympics edition of American Cinematographer because it represented a major technological advancement: the first live television broadcast. However, it contained little information on the lenses used. Unlike today, the options were still limited. From advertisements showing camera operators in action in the magazine, Förderer noticed that they often used telephoto lenses. But the sets for his shoots were confined spaces, so he needed wider focal lengths. He eventually discovered that the Voigtländer company had created the first zoom lenses for 35mm cameras, as well as the first zoom lenses for 16mm and 35mm, the Zoomar. As fate would have it, this company was based in Munich, like the 1972 Olympics, which Förderer interpreted as a sign. He wanted to avoid modern lenses with high contrast and definition, instead seeking soft contrast and real texture to recreate the smoky atmosphere, since smoking was widespread at the time, without fear of a “dirty” image. As much of the film takes place in the control room, a confined space, lenses with a decent focal length and a good minimum focal length were needed. Finally, Förderer sought a sense of volume and depth, so that faces would stand out against the backgrounds. He attributes this three-dimensional effect to the pronounced focus fall-off and barrel distortion of certain lenses.

The “smoky” texture of the control room

A DIY “detuning” Förderer tested classic vintage lenses (Cooke, K-35) but quickly dismissed them. “They were beautiful, but also too beautiful, with golden flares… it didn’t seem right for such a serious subject.” They were also too heavy and their mechanics unreliable for the fast zoom movements he envisioned. A few rare re-cased versions of the original Zoomars exist. But he ultimately opted for a more radical solution: buying two original lenses on eBay, which he preferred for their compactness and lightness, even if they didn’t have a good close focus. At the time, manufacturers sought to produce the most perfect lenses possible, but today, in digital, cinematographers are more inclined to use older lenses precisely to rediscover “flaws.” That’s how he decided to detune them himself.

Voitlander Zoomar 36-82mm T2.8

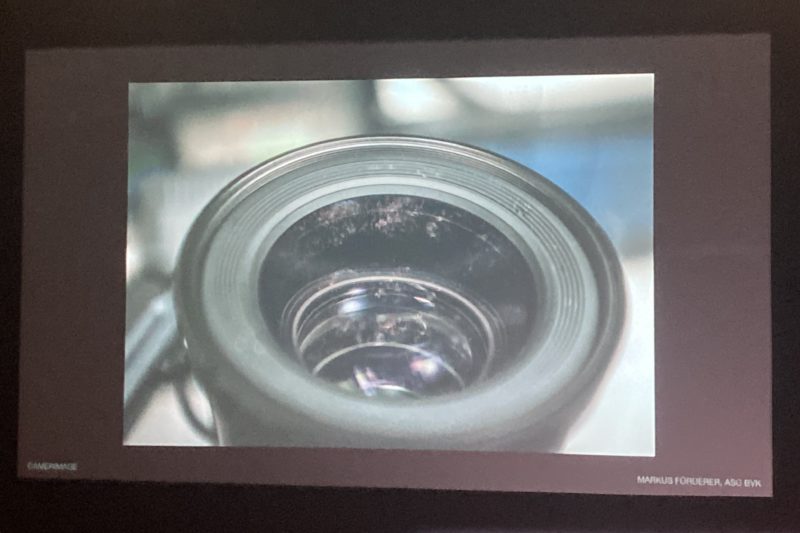

He even went further in his search for texture: “I literally put my fingerprints on every lens element… I kept the center clear… and I added dust particles.”

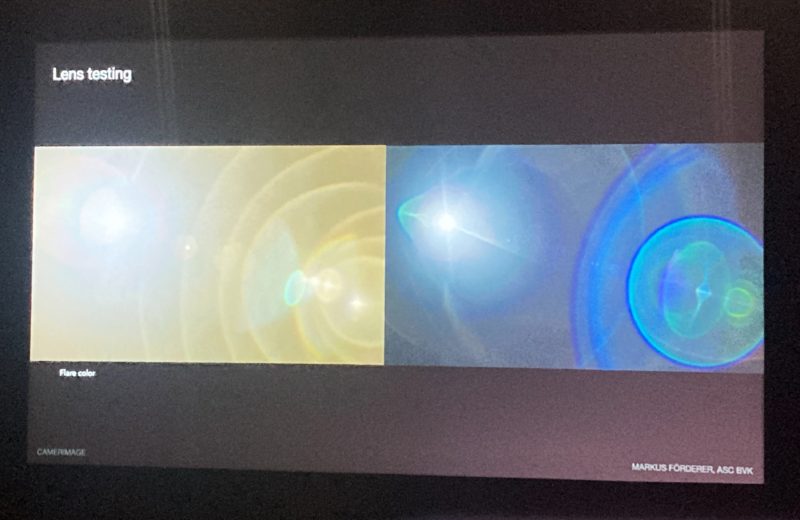

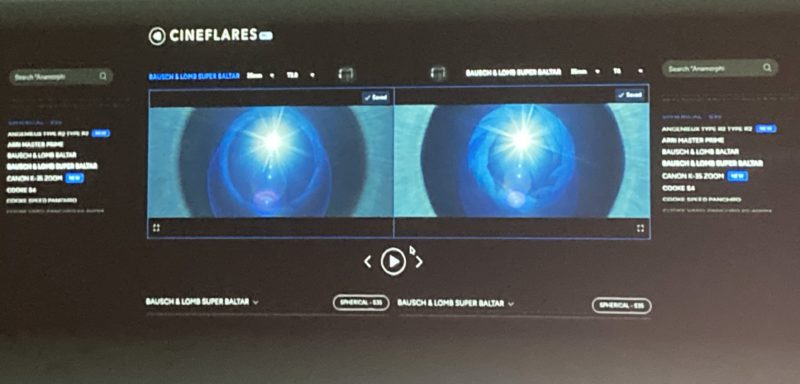

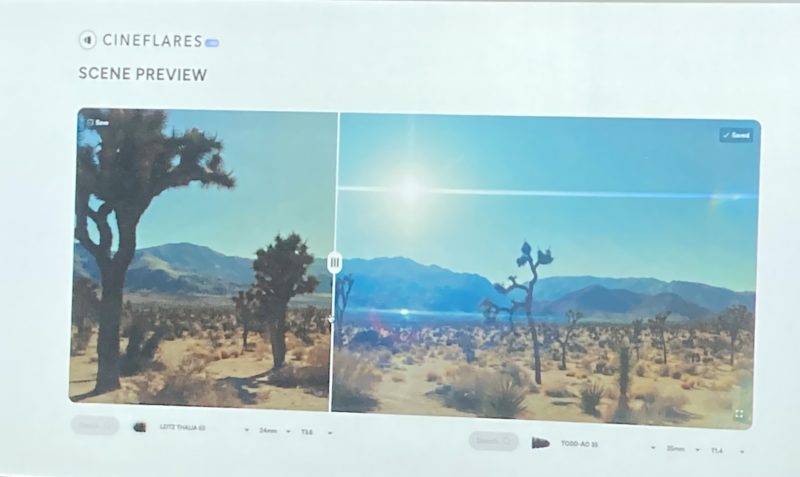

To add texture to the image, Förderer left fingerprints on the lenses. The anecdote is delightful: “It took me all day to reassemble it, and nothing worked. The focus, the zoom, everything was jammed.” The savior was Manfred Jahn, head of the optics department at ARRI Rental Munich. “I gave him the lens and said, ‘Can you get it working? But please, don’t touch the lenses!’ He came back 15 minutes later, and the lens worked like new.” The result: a unique look, with a subtle milky diffusion and warmer flares, which he couldn’t achieve with any standard lens. Anamorphic lenses as a tool for tension. The majority of the film is shot in spherical with these “detuned” zooms, supplemented by a Zoomar 90mm Macro-Kilar for close-ups and a P+S Teknic zoom. Furthermore, Förderer always kept a set of anamorphic lenses on hand: “We had anamorphic lenses ready whenever the tension rose,” he explains. It wasn’t systematically planned, but rather an intuitive decision made on set. “The camera allowed it… it’s just a matter of pressing a button, no restarting, nothing.” His secret tool: “Cineflares,” the “ShotDeck” of lenses. To objectify his choices and meticulously compare lenses, Markus Förderer doesn’t rely on traditional tests. He revealed that he spent years building his own platform: Cineflares.com.  “I started building this platform years ago.” “It’s a database where I began capturing lens renderings, initially just flare, all filmed using motion control in a controlled environment.” His observation was simple: the usual tests at rental companies lack rigor. “Sometimes you see an assistant in a test room with a flashlight… but every angle where you change the light makes the result very different,” he explained. “I realized that to truly analyze a lens and make an informed decision, I had to compare.” The human eye isn’t very good at pure evaluation, but it excels at comparison: faced with two options, we can say which one we like better and why.

“I started building this platform years ago.” “It’s a database where I began capturing lens renderings, initially just flare, all filmed using motion control in a controlled environment.” His observation was simple: the usual tests at rental companies lack rigor. “Sometimes you see an assistant in a test room with a flashlight… but every angle where you change the light makes the result very different,” he explained. “I realized that to truly analyze a lens and make an informed decision, I had to compare.” The human eye isn’t very good at pure evaluation, but it excels at comparison: faced with two options, we can say which one we like better and why.

[caption id="attachment_12880" align="alignnone" width="800"]  Comparing the same lens at two different stops

Comparing the same lens at two different stops

Cineflares allows him to compare lenses side-by-side, synchronized by timecode. It’s possible to: Search by film name. Compare the same lens at different T-stops. Analyze flares, bokeh, and even “scene previews” to see the rendering in a real-world situation. Today, before even going to the rental shops, he browses this database, and once he has selected three or four lenses, he goes to the rental shop to test them specifically for the project.

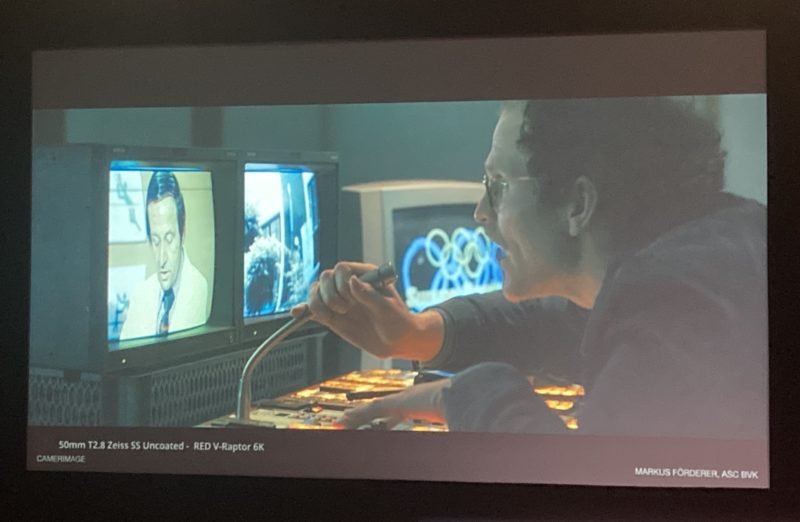

LensFlare allows for comparison on a real shot. A sense of real time. Initially, the film was to be shot on film. This choice seemed obvious since the story takes place in the 1970s. However, Förderer knew that Tim Sutton, the director, liked to do long takes. On the other hand, the shot breakdown was generally not determined beforehand. “We wanted to capture [the scenes] as if we were a documentary crew, observing what was happening. Our idea was to follow the events in real time, like the characters. So, what we did was have Tim Sutton, the director, and the actors discuss the scene, but we never did a real setup. We did, of course, have an idea of what someone would probably be looking at on the main monitor in that scene, but we didn’t rehearse and we shot the whole scene in one take, with two cameras, always with the intention of shortening it in the editing room.”  There was indeed talk for a long time of making the film in a single take, but Förderer disliked this approach because certain actions, particularly movement, can appear very long on screen even though their duration is uninteresting, thus disrupting the rhythm and tension. Moreover, “the film explores the theme of media and the power of images, so editing—what you show, what you don’t show—is very important. We knew we also wanted to play with editing. But we filmed everything in one long take to create that energy.” To allow for 360° shots and minimize lighting setup time, thus giving the actors as much screen time as possible, the lighting was integrated into the set design as much as possible. At the time, tungsten and neon sources were used, but Förderer made use of LED bulbs and tubes in order to be able to easily and quickly control intensity and color temperature, including sometimes changing them during a shot according to the camera axes.

There was indeed talk for a long time of making the film in a single take, but Förderer disliked this approach because certain actions, particularly movement, can appear very long on screen even though their duration is uninteresting, thus disrupting the rhythm and tension. Moreover, “the film explores the theme of media and the power of images, so editing—what you show, what you don’t show—is very important. We knew we also wanted to play with editing. But we filmed everything in one long take to create that energy.” To allow for 360° shots and minimize lighting setup time, thus giving the actors as much screen time as possible, the lighting was integrated into the set design as much as possible. At the time, tungsten and neon sources were used, but Förderer made use of LED bulbs and tubes in order to be able to easily and quickly control intensity and color temperature, including sometimes changing them during a shot according to the camera axes.  Multiple formats in a single camera. Furthermore, there was the issue of monitors, which were very prominent in the image and quite diverse. Finally, the cinematographer considered it important to capture in the film the aesthetic of the different formats used at the time for this type of event: analog video, 16mm, and 35mm. Thus, the film wasn’t fixed in a single look, reflecting what was happening in the different scenes. The flexibility of the RED Raptor, with its multi-format sensor, quickly emerged as the obvious choice. Cropping in the 8K sensor allowed for a depth of field similar to 16mm and analog.

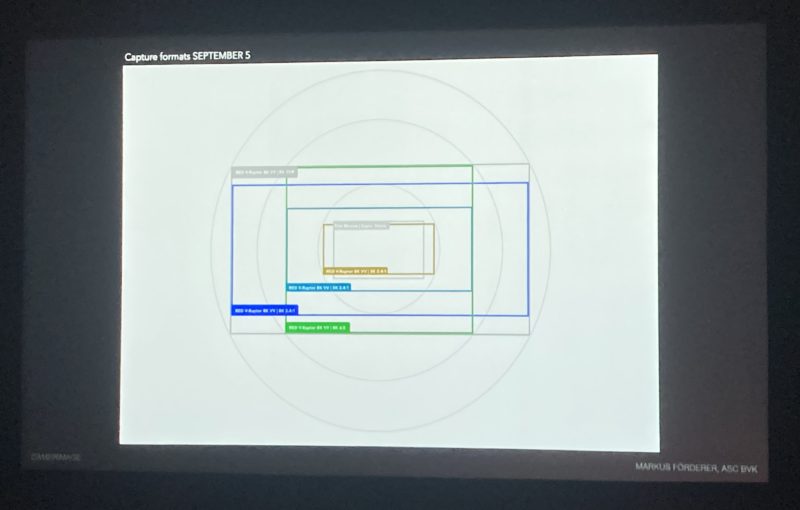

Multiple formats in a single camera. Furthermore, there was the issue of monitors, which were very prominent in the image and quite diverse. Finally, the cinematographer considered it important to capture in the film the aesthetic of the different formats used at the time for this type of event: analog video, 16mm, and 35mm. Thus, the film wasn’t fixed in a single look, reflecting what was happening in the different scenes. The flexibility of the RED Raptor, with its multi-format sensor, quickly emerged as the obvious choice. Cropping in the 8K sensor allowed for a depth of field similar to 16mm and analog.

[caption id="attachment_12883" align="alignnone" width="800"]  The different sensor formats used by Markus Förderer on 5 September

The different sensor formats used by Markus Förderer on 5 September

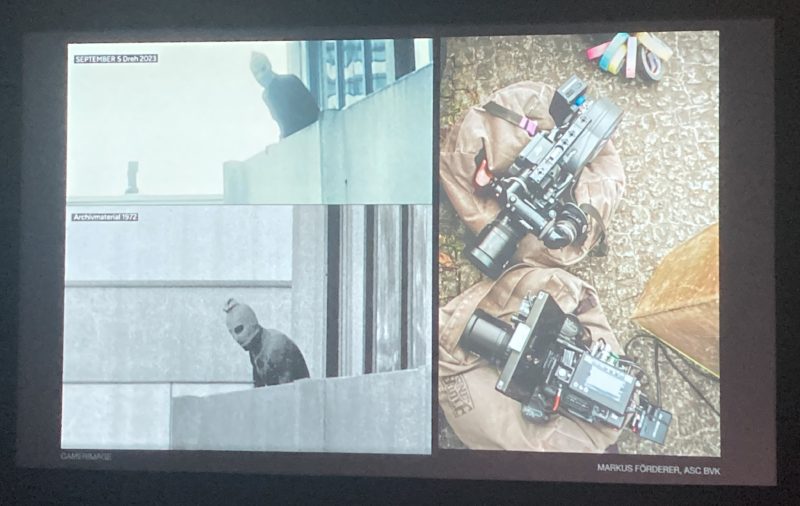

The making of fake archives One of the biggest technical challenges concerned the monitors in the control room. Due to rights issues or the absence of images, the team had to recreate what they were broadcasting. “Nearly 80% of what you see on the TVs in the control room is recreated,” reveals Markus.  To achieve the grainy, low-definition look of 1970s PAL analog video, the process was ingenious: the fake archival footage was shot with the Red in 8K, but using the highest possible RAW compression to degrade the image. This degraded signal was then fed into a genuine vintage PAL monitor, and they subsequently re-filmed this TV screen with the Red 8K camera. This process allowed them to capture the true pixelation and imperfections of the cathode ray tube, while maintaining control and flexibility, and requiring only one camera for the shoot.

To achieve the grainy, low-definition look of 1970s PAL analog video, the process was ingenious: the fake archival footage was shot with the Red in 8K, but using the highest possible RAW compression to degrade the image. This degraded signal was then fed into a genuine vintage PAL monitor, and they subsequently re-filmed this TV screen with the Red 8K camera. This process allowed them to capture the true pixelation and imperfections of the cathode ray tube, while maintaining control and flexibility, and requiring only one camera for the shoot.  A subliminal “Flicker” to heighten the tension. Initially, Förderer wanted to illuminate the control room by letting light in through the windows. But the director didn’t want any openings to the outside, in order to create a feeling of claustrophobia. As a result, the monitors became the main light source in this set.

A subliminal “Flicker” to heighten the tension. Initially, Förderer wanted to illuminate the control room by letting light in through the windows. But the director didn’t want any openings to the outside, in order to create a feeling of claustrophobia. As a result, the monitors became the main light source in this set.  The cinematographer wanted to avoid the perfect “look” of modern cinema monitors, where flicker is eliminated. “I read studies… when you pulse light at certain frequencies, it affects the heart rate, it raises it,” he explains. So he kept the on-screen monitors synchronized using the shutter (without visible flicker so as not to attract too much attention and distract the viewer), but hid Astera tubes above the set, concealed by yellow curtains, which subtly pulsed. “We programmed different flicker frequencies… we could dynamically… change the frequency” to discreetly increase physiological tension. He even had the neon lights in the corridors replaced with LED tubes and programmed them by segmenting them to mimic the flicker effect at the ends characteristic of fluorescent tubes at the end of their lifespan. This did not change the overall exposure, but brought a slightly “dirty” dimension to the image, which contributed to the effect of realism – let’s not forget that all the sets were recreated in the studio.

The cinematographer wanted to avoid the perfect “look” of modern cinema monitors, where flicker is eliminated. “I read studies… when you pulse light at certain frequencies, it affects the heart rate, it raises it,” he explains. So he kept the on-screen monitors synchronized using the shutter (without visible flicker so as not to attract too much attention and distract the viewer), but hid Astera tubes above the set, concealed by yellow curtains, which subtly pulsed. “We programmed different flicker frequencies… we could dynamically… change the frequency” to discreetly increase physiological tension. He even had the neon lights in the corridors replaced with LED tubes and programmed them by segmenting them to mimic the flicker effect at the ends characteristic of fluorescent tubes at the end of their lifespan. This did not change the overall exposure, but brought a slightly “dirty” dimension to the image, which contributed to the effect of realism – let’s not forget that all the sets were recreated in the studio.  Low-Tech Ingenuity: The Model Helicopter. Faced with budget constraints, Markus prioritized on-camera effects instead of resorting to expensive VFX. Moreover, the special effects shots often need to be filmed “cleanly” to facilitate their integration in post-production, but it’s often difficult to make them blend well with the rest of the film, especially when the film has a pronounced, degraded texture like the one Förderer wanted. When you’re just shooting a clean shot, you don’t necessarily think about the effects that add realism; you need to experiment, to make mistakes on set for that. “A good example is Ridley Scott’s film Alien, a man in a rubber suit. You watch it for four frames and think, ‘That’s ridiculous.’ But the only way to film that interestingly is to have a man in a rubber suit, and then you realize, ‘Oh, we need smoke. We need to underexpose.'” “You need strobe lights.” And that’s how you create that magic. If you simply film a smoke-free, light-free corridor and add a perfectly realistic CGI alien, it will still look like a CGI alien, and that’s not scary. In September 5th, some sequences feature helicopters, but flying them in the set wasn’t permitted; not to mention the cost. However, 3D was expensive, and the result risked being disappointing. “I can almost always tell when a helicopter is CGI. It’s very difficult.” The solution? “What you see is a remote-controlled miniature helicopter.” “I mentioned it in a production meeting, people thought I was crazy… The guy [the miniature pilot] wanted 500 euros. I told the production team, ‘Hire him. If it doesn’t work, I’ll pay out of my own pocket.’” Filmed from the right angles with an old telephoto lens bought on eBay, the illusion was perfect. Since the helicopter looked tiny on screen, Förderer had the intuition to move it behind the TV tower. A quick rotoscoping made it appear larger. In the end, the production team was convinced and brought the mini-helicopter pilot back for more than initially planned. The team also filmed the model from all angles to allow the VFX team to recreate it in 3D and integrate it into other shots.

Low-Tech Ingenuity: The Model Helicopter. Faced with budget constraints, Markus prioritized on-camera effects instead of resorting to expensive VFX. Moreover, the special effects shots often need to be filmed “cleanly” to facilitate their integration in post-production, but it’s often difficult to make them blend well with the rest of the film, especially when the film has a pronounced, degraded texture like the one Förderer wanted. When you’re just shooting a clean shot, you don’t necessarily think about the effects that add realism; you need to experiment, to make mistakes on set for that. “A good example is Ridley Scott’s film Alien, a man in a rubber suit. You watch it for four frames and think, ‘That’s ridiculous.’ But the only way to film that interestingly is to have a man in a rubber suit, and then you realize, ‘Oh, we need smoke. We need to underexpose.'” “You need strobe lights.” And that’s how you create that magic. If you simply film a smoke-free, light-free corridor and add a perfectly realistic CGI alien, it will still look like a CGI alien, and that’s not scary. In September 5th, some sequences feature helicopters, but flying them in the set wasn’t permitted; not to mention the cost. However, 3D was expensive, and the result risked being disappointing. “I can almost always tell when a helicopter is CGI. It’s very difficult.” The solution? “What you see is a remote-controlled miniature helicopter.” “I mentioned it in a production meeting, people thought I was crazy… The guy [the miniature pilot] wanted 500 euros. I told the production team, ‘Hire him. If it doesn’t work, I’ll pay out of my own pocket.’” Filmed from the right angles with an old telephoto lens bought on eBay, the illusion was perfect. Since the helicopter looked tiny on screen, Förderer had the intuition to move it behind the TV tower. A quick rotoscoping made it appear larger. In the end, the production team was convinced and brought the mini-helicopter pilot back for more than initially planned. The team also filmed the model from all angles to allow the VFX team to recreate it in 3D and integrate it into other shots.  Dark night and printed backdrop. In the final scene at the airport, the hostages are taken there at night. The film remains from the perspective of the journalists, who are far from the action and unsure of what is happening; the suspense of whether they have been freed and are still alive lasts for a while. A shootout erupts.

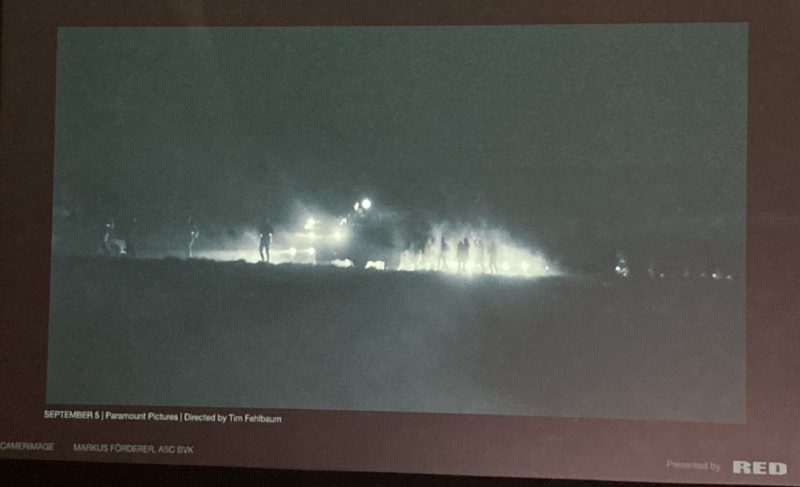

Dark night and printed backdrop. In the final scene at the airport, the hostages are taken there at night. The film remains from the perspective of the journalists, who are far from the action and unsure of what is happening; the suspense of whether they have been freed and are still alive lasts for a while. A shootout erupts.  The actual location is now unrecognizable, which severely limited the possible angles. Recreating it in 3D seemed too expensive, especially since little would be visible at night and given its remoteness. Förderer opted to recreate the very dark aesthetic of the archival footage from that time, where little is discernible. Since it was a very remote location, without streetlights, and the cinematographer couldn’t create artificial moonlight or use helicopters, he proposed shooting entirely in black and white. This allowed for the use of a very high camera sensitivity, 6400 ASA, or even higher at times, so that car headlights could serve as light sources.

The actual location is now unrecognizable, which severely limited the possible angles. Recreating it in 3D seemed too expensive, especially since little would be visible at night and given its remoteness. Förderer opted to recreate the very dark aesthetic of the archival footage from that time, where little is discernible. Since it was a very remote location, without streetlights, and the cinematographer couldn’t create artificial moonlight or use helicopters, he proposed shooting entirely in black and white. This allowed for the use of a very high camera sensitivity, 6400 ASA, or even higher at times, so that car headlights could serve as light sources.  “It was like a traffic jam where the viewers started looking towards the airport where the shootout was taking place. So we used the car headlights, and with my lighting team, we hid battery-powered LED spotlights between the headlights to create silhouettes. And we had smoke machines, because back then, these cars—most of them old cars—threw out a lot of smoke. So we enhanced that effect by spreading out battery-powered smoke machines. It was a very long road. This way, we were able to shoot 360 degrees without seeing any Condors [helicopters], any filming equipment.” Furthermore, detuning the lenses created a halo of light that masked the light sources in the frame, also contributing to an analog look. A gaffer also followed the frame with normal lighting, using a kind of Chinese lantern to illuminate faces as the camera moved closer to the characters. In color, the rendering was not good at all, but in black and white, pushing the sensor so far really gave a 16mm effect. As for the airport in the distance, Förderer quickly ruled out the use of a blue screen, again to avoid having to shoot too cleanly, because his intuition was that this sequence should be shot handheld, and he wanted to be able to zoom through the fence.

“It was like a traffic jam where the viewers started looking towards the airport where the shootout was taking place. So we used the car headlights, and with my lighting team, we hid battery-powered LED spotlights between the headlights to create silhouettes. And we had smoke machines, because back then, these cars—most of them old cars—threw out a lot of smoke. So we enhanced that effect by spreading out battery-powered smoke machines. It was a very long road. This way, we were able to shoot 360 degrees without seeing any Condors [helicopters], any filming equipment.” Furthermore, detuning the lenses created a halo of light that masked the light sources in the frame, also contributing to an analog look. A gaffer also followed the frame with normal lighting, using a kind of Chinese lantern to illuminate faces as the camera moved closer to the characters. In color, the rendering was not good at all, but in black and white, pushing the sensor so far really gave a 16mm effect. As for the airport in the distance, Förderer quickly ruled out the use of a blue screen, again to avoid having to shoot too cleanly, because his intuition was that this sequence should be shot handheld, and he wanted to be able to zoom through the fence.  The solution? “It’s not even a miniature, it’s a printed photo.” The team simply photographed the location, added vintage cars and helicopters. The large-format print was placed 50 meters from the camera, lit from the front, with the windows backlit; a little smoke and that was it. At such distances, there are no real 3D or parallax effects, and the presence of the barrier and the characters in the foreground contributed to a sense of depth. Having this setup during filming allowed them to adjust levels and contrasts to achieve a realistic look, while giving the actors considerable freedom in terms of camera angles.

The solution? “It’s not even a miniature, it’s a printed photo.” The team simply photographed the location, added vintage cars and helicopters. The large-format print was placed 50 meters from the camera, lit from the front, with the windows backlit; a little smoke and that was it. At such distances, there are no real 3D or parallax effects, and the presence of the barrier and the characters in the foreground contributed to a sense of depth. Having this setup during filming allowed them to adjust levels and contrasts to achieve a realistic look, while giving the actors considerable freedom in terms of camera angles.  For such a choice, you obviously need a director and a production designer who are on board. Since the production wasn’t convinced, the director of photography conducted tests with a 1.5-meter version provided by the set design department, at night in the production’s parking lot. Förderer concluded his presentation by taking the opportunity to encourage the audience to experiment: “I can only encourage you to be bold. I think that right now, with AI-generated images, it’s precisely the human touch, what makes things imperfect, that sometimes makes the difference. What makes things human, manual, tactile—I think the audience will eventually feel it and find it more human. And that’s why, I hope, we all go to the cinema to watch films.” »

For such a choice, you obviously need a director and a production designer who are on board. Since the production wasn’t convinced, the director of photography conducted tests with a 1.5-meter version provided by the set design department, at night in the production’s parking lot. Förderer concluded his presentation by taking the opportunity to encourage the audience to experiment: “I can only encourage you to be bold. I think that right now, with AI-generated images, it’s precisely the human touch, what makes things imperfect, that sometimes makes the difference. What makes things human, manual, tactile—I think the audience will eventually feel it and find it more human. And that’s why, I hope, we all go to the cinema to watch films.” »

https://lenses.cineflares.com/

On Zoomar:

https://www.cameraquest.com/ekzoom.htm

Interview with Markus Förderer on Film Makers’ World:

Inside the Cinematography of September 5 with Markus Förderer ASC

A podcast in English about his work on the film:

https://themakingof.substack.com/p/september-5-cinematographer-markus

Article from Cinematography:

https://www.cinematography.world/forderer-recreates-chilling-events-of-september-5-with-dopchoice/

An article in English about the production designer’s work on the film:

Production design of “September 5” – interview with Julian R. Wagner