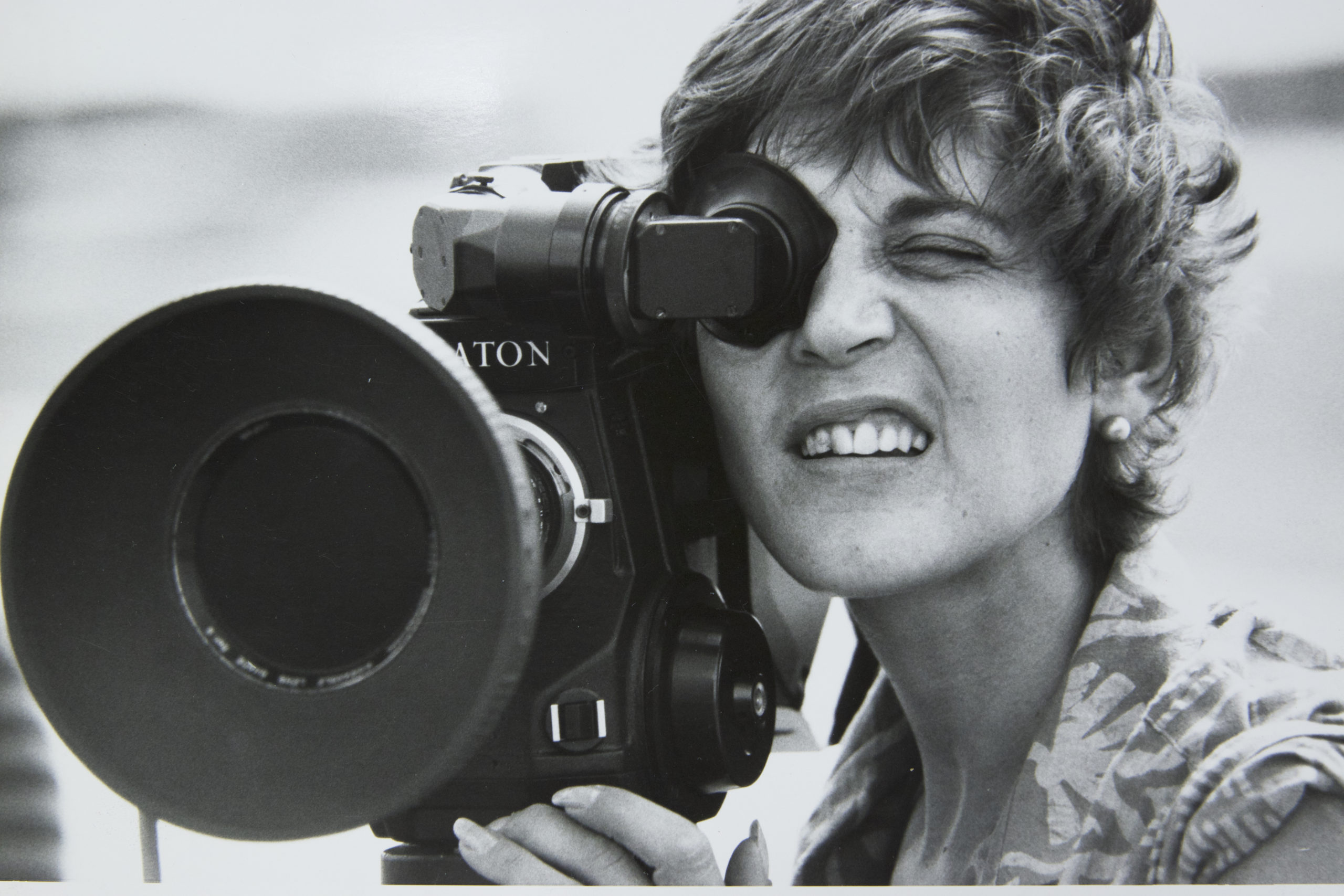

Nancy Schreiber, ASC is an award-winning cinematographer. Her career is an inspiration for many of us. She accepted to answer a few questions for the UCO.

You are one of the first female cinematographers in the world. When did you start?

I’m still shocked to learn that statistic that I was one of the first. It never seemed like it should be a gender based profession… I fell into it, really: I have a psychology degree from a great American university (University of Michigan) as well as a minor in History of Art and I was taking many stills at the end of high school and through college. It was during a time of political and racial unrest and I was an activist.

This was a time of race riots, the anti-war movement, and the second wave of the feminist movement. I started making little Super-8 films with a women’s collective. When I decided not to become a therapist, I moved to New York, where I knew film would be part of my life. Instead of going to film school, I answered an ad in an underground newspaper, the Village Voice to be a production assistant. Miraculously, on that movie, I worked in the electric department and fell in love with the endless possibilities of creating light and shade, and this along with learning about electricity. In those days in New York, we did not use generators, and I had to ‘tie in’ to the main panels with clamps and cables.

Looking back, it was not the safest practice to use but I learned quickly and was fearless. From there I went on to first being a set electric and best boy for NY gaffers in films and commercials and a gaffer on documentaries, where I often had to AC and load mags as well. I definitely looked beyond any sexism that existed. It was there, but fortunately there were some men not afraid to let a woman do this kind of work.

It never occurred to me that I couldn’t be a gaffer. There were other women shooting at this time in documentaries and I often got to work with them.

Did you always know you wanted to be a DOP? How did you discover this particular job and what decided you to start?

Is there a movie you fell in love with?

I remember my older brother and sister took me to the art movie theater in Detroit, where we watched Lawrence of Arabia. The visuals of that film were imprinted on my brain and soul. It may be why I picked up a still camera in high school. My dad, who passed away when I was 11, always took 8mm videos of the family, but it didn’t occur to me until years later that I had been influenced unconsciously by him in my choice of career.

I sometimes regret not going to film school for the camaraderie and connections I missed, but I did get to shoot Columbia University student films, as they don’t have a cinematography program. But I earned while I learned… on set and from so many generous and talented professionals.

How hard was it to find your place in the industry?

It was terribly difficult. The work was all in documentaries. I had to raise the money and make my own film, just to show that I could shoot handheld. The film was successful on the film festival circuit, and after that, I made a feature documentary and an art dance film, and people wondered what I was going to pursue. In those days, unlike today, one couldn’t be a DP and a director, particularly if you were a woman. It was suggested that people would think I was a dilettante. My choice was clear. I have always been visually focused. Somehow I ‘clawed’ my way back into the narrative and took what I could get! I’m grateful for the documentary world, however, as I still enjoy going back and forth across genres. My skills, shooting handheld and working quickly, certainly paid off later in music videos and episodic TV, where handheld is still the rage.

You are the 4th woman to join the ASC: how did it change your career? Did you get more propositions after that?

Please tell us more about this period.

It really didn’t change my career. Producers and directors did not seem to be interested or even aware, at the time I was coming up. Finally, of course, the world started to recognize the imbalances in our industry for women, women-identifying and diverse or underserved groups. It is still shockingly imbalanced. There have been baby steps moving forward, but then stagnation or a backlash seems to happen. I’m proud that the ASC and other societies around the world have opened their doors and minds to the great talent out there that needs to be recognized. We just have to dig in the lower budget world to see the immense creativity out there.

You come to cinematographers festival (Camerimage, Manaki…) almost every year. For sure you saw the evolution of the point of view, the way to narrate with images and the style of images:

Just as history repeats itself, style goes in trends, keeps evolving, and repeating. What is old is new again.

There have been trends that come and go, and come and go yet again, such as 3D. We all thought virtual production would be more industry-wide but often financial limitations have made it out of reach for many. Plus, although we would be thrilled to have our VFX elements so early, production has had a hard time with getting VFX elements planned in advance. And we do love going on location, mixing it up with stage and studio work.

We are loving the current explosion of Anamorphic! When I started shooting, anamorphic lenses weren’t very plentiful. When I photographed Your Friends and Neighbors for director Neil LaBute, with an amazing cast (Ben Stiller, Catherine Keener, Aaron Eckhart, Jason Patric, Nastassja Kinski, and Amy Brenneman), we wanted to shoot in Anamorphic. Our producers wouldn’t agree, as they believed we would need too much light for all our interior work. (The film has not one exterior shot.)

Film stocks were slow, and the anamorphic lenses needed a deeper stop than many lenses today. And they worried we would require more days than the 20 they gave us. We did shoot wide-screen, Super 35, but there were no Digital intermediates in those days. We had to make an inter-positive and an internegative in the photochemical process, losing a generation. Trivia: Your Friends and Neighbors was the very first film ever reviewed on Rotten Tomatoes (and we got mixed reviews). That film was special for me as I got to attend all the rehearsals, and the actors loved the rehearsal process. It is stuck in Standard Def as our distributor got sold and no one wants to pay for an uprez to 4k. I’m looking into AI to help with resolution and get rid of the artifacts, hopefully for free.

Also when I started, Zeiss Superspeeds were so inexpensive. I regret not buying any. On my early smaller films, if for example, I went through Panavision, I would rent a lens package of Primos but would add Superspeeds for my night exterior work. I couldn’t afford a lighting package and lifts for large night exteriors and the proper lifts and crew for the Primos to be used at night. Today, I treasure the beautiful look of Superspeeds when combined with our digital cameras. The inherent softness counteracts any harshness from the sensor, humanizing our images.

Would you mind giving us your feelings about the changes that have happened in the industry since the time you started, especially for women?

When I started as an electrician many decades ago, and then progressed to gaffer and DOP, I would never have believed the progress would be so slow for acceptance and inclusion. New York in the 70s and 80s was almost affordable, with an art, dance, film and music scene very open to experimentation, and there was often funding for it. I wonder, had I started in Los Angeles, if I would still be shooting these days, as Hollywood was—and is—such a closed society, a tight network of mostly rich and white men. There has been tokenism. Women have excelled in documentaries in all areas. Budgets are lower. How could we not succeed when we have a schedule of more than 18 or 20 shoot days, with a large crew, including a full pre-rigging crew?

Can you tell us your feelings about the changes you saw when digital cameras appeared—for you as well as in the industry in general.

As DOPs, we naturally are interested in any technical advances that come along. Early digital cameras were challenging, but we learned how to work with them as they evolved. And today I am grateful for the innovations our manufacturers have achieved. We can work with sensors allowing high ISOs combined with low levels of light. Along with major leaps forward with our cameras, the explosion of LEDs and their improved accuracy in color rendition keep our sets cooler. Not only beneficial for our cast and crew but also for the health of the planet with less consumption of power. Now with AI, that trend is unfortunately being reversed. I do still use large fresnels, such as 20ks, and large HMI should I have large windows to come through.

Which one of the films you shot is your favorite? With which director did you have the best/favorite collaboration? Tell us more about the process during this particular collaboration.

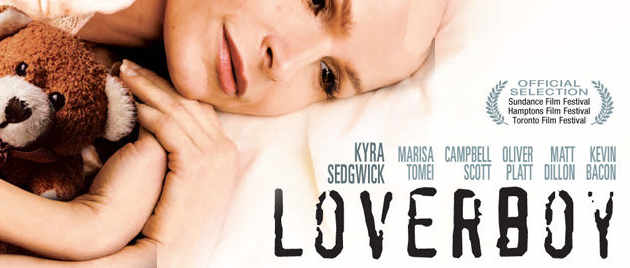

This is a difficult question. Often my favorite film or tv project is a combination of the director and the cast and crew I’m working with, as well as smart producers who understand our needs and help make it happen for us. I must say that getting the chance to work with Kevin Bacon directing his wife, Kyra Sedgwick, on Loverboy was a gift. Kevin was so organized, so open, and so smart.

We were still shooting in film in those days. What a cast! Matt Dillon, Oliver Platt, Marisa Tomei, and Sandra Bullock. Ms. Bullock played the neighbor of Kyra’s when she was young, and her young self was played by Kevin and Kyra’s daughter, Sosie Bacon, still an actress today. I took some risks on the flashbacks with the bleach bypass process. I did tests, and the producers supported us, knowing this photochemical process would be permanent. No DIs in those days, and there was TRUST and RESPECT for our artistic vision, without as many “opinions”.

As for episodic, I loved working with Karena Evans the pilot director on Starz’ (American TV channel) P-Valley. Karena had come out of filming Drake music videos and we worked well pushing the envelope when determining the look for the whole series, in terms of color, contrast framing and movement ideas. I think the lookbook was 72 pages of images.

Also I loved working with director Tom Verica when he came in to direct an episode of Station 19 for Shondaland. His energy was contagious, so uplifting, and although he worked fast, we always found ways to not sacrifice the visuals. (Tom has gone on to produce and direct Bridgerton and Queen Charlotte)

What is your approach / process when starting a new project (from reading the script)? What is your approach for creating the images (about light, framing, colors, and collaboration with costume and set design)? How do you use those parameters to create the «visual world» of the movie?

First of all I read the script several times before making any judgments. I really want to get to know the characters, their motivations, their psychology, their arcs as the film progresses. I try to see the movie in my “mind’s eye” first. Then I might pull images from films, including ones I have shot. Or photography or paintings that might relate to the script. I’ll make or revise my look book as preproduction progresses. I love my prep time, working with a director on the marriage of substance and style. This period of germination is very freeing, and exciting. We might break down the script into emotional beats and will shotlist once we have some locations locked or sets designed. Of course this is just a blueprint, as it changes once we are on set and block the actors. I like to storyboard action scenes or car chases. I’ll share my lighting ideas and plots and needs for special equipment but encourage an openness as my grip and electric keys plan. It is important for me to work with the production designer and costume designer as early as possible to collaborate on any practical lighting to be built-in, practical lamps, to test wardrobe and wall colors, while I do my lens and camera tests. I love spending time in the art department in prep as they often are hired before I am and have already done in-depth research that adds to my inspiration.

Any advice for the next generation?

Try to get as much on set experience as possible. Don’t be discouraged if you don’t get a particular job. You can’t take it personally as there are many factors that go into the hiring process. Plan with as much detail as you can, as that will help you be more free when you are in production. Go to museums and galleries and music in your free time or be in nature and watch how the light changes all day. Have balance in your life between work and play. If you have such a deep passion for our profession, as I do, you won’t give up when obstacles come your way and you will thrive in life and work.